Julian David Layton was born into a German Jewish family in 1904; his parents had migrated to England from Frankfurt in 1893.

In the early 1930s Layton worked as a stockbroker initially, mainly in Germany and France – he was fluent in both French and German. The Loewenstein family (as it was originally) were on good terms with the Rothschild family, who were crucial to later rescues of Jews from Europe, including the Kindertransport and Kitchener camp, as well as smaller schemes such as the ‘Cedar Boys’ rescue to a house on one of the Rothschild estates.

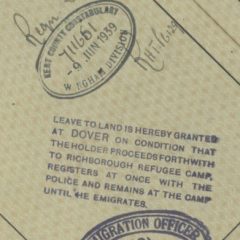

From around 1934 Layton was sent to help select German and Austrian Jews for migration – especially to the British colonies. He was known and valued for his tact and diplomacy. From the Anschluß to the outbreak of war, he spent most of his time on this task in Vienna at the offices of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde (IK) – a Jewish aid agency and the Austrian equivalent of the Reichsvertretung in Germany.

When war was declared and many of the Kitchener men joined the British Army, around 1,200 were left as civilian residents in Kitchener camp – until around summer 1940. Some were too young to enlist, some were too elderly, or failed the medical (often because of injuries sustained in concentration camps in 1938); some did not wish to join up because they still hoped to be able to use their visas to emigrate onwards, and some would not fight for religious or other ethical reasons. For example, Hans Jackson, whose paintings are reproduced across this site, was too young to enlist, but he was employed on a ‘listening post’ in Haig camp (see below), translating German messages as part of the war effort. The medics in the camp were told to enlist in the RAMC rather than in the Pioneer Corps, so there was a wide range of outcomes even at this point.

Copied with the kind permission of Brian Janes and the Colonel Stephens Railway Museum website

Around 700 of these men had visas to emigrate on to the USA or Palestine, although the CBF Minutes observe that at least 200 of these for the US alone did not have the funds to do so, and CBF funds to help with this were by now running critically low (14 December 1939).

The frustration of this situation meant that tempers were running high. Layton was called upon once again, therefore, and arrived in the middle of October 1939. He stayed at the Bell Hotel in Sandwich to start with, where Phineas May had stayed when he first arrived there. Layton attended to the pastoral care needs of the remaining men as best he could under the circumstances, and by all accounts was successful at defusing the tense standoff that had arisen.

At base, the camp management team had been concerned that the remaining men should not become a drain on the public purse now that war had broken out, as the CBF had originally undertaken to ensure. They also needed the residents’ practical assistance to help run the military training side of Kitchener (which was now a Pioneer Corps training ground). These men, meanwhile, wanted to be able to move freely out of the camp. The camp organisers were extremely annoyed that more of the men had not joined up, and the men were annoyed at the increased restrictions imposed on them: they threatened strike action. Whatever the reality of what went on in the camp over these months between the outbreak of war and early summer 1940, Layton’s presence seemed to smooth things over to the extent that the whole scheme ran more smoothly again and talk of a strike dissipated.

After the military disaster at Dunkirk and the change in national mood against the German-speaking refugees, many of these men who had not joined the army were sent to internment camps. Layton accompanied the men to the Isle of Man. He stayed in a hotel in Ramsey to remain near them and to help as much as he could: he bought them extra food rations from the town, and drew attention as best as he could to the problems arising because of a lack of kosher provision.

Some of these men were deported on HMT Dunera, on a brutal voyage that was so badly mismanaged that eventually some of the troops in charge of the refugees and prisoners were court-martialled and the British government paid out compensation to many of those affected. Once again Layton was called upon after this voyage, partly because he had experience with the administration in Australia. He had visited during the 1930s to persuade the Australian government to accept more German Jewish refugees.

Layton was sent to assist the men who had been so badly affected on the Dunera and to help obtain the compensation for losses suffered. Now a Major, he arrived in early 1941 to negotiate for the men to be allowed again the opportunity to join the Pioneer Corps (or the Australian Army), or to return to Britain, for those who wished to do so. He succeeded in getting hundreds of the men released from internment. To assist those who did not obtain release, Layton remained in Australia until January 1945.

In a final act for the Kitchener camp rescue, in June 1971 Layton attended a ceremony for the unveiling of a plaque in Sandwich to commemorate Kitchener camp and the thousands of lives it saved. He drew back the small curtain to unveil the plaque while others who had been instrumental in the scheme looked on.

…………………………….

Sources

CBF Minutes, 1938-1939, at the Metropolitan City archives, London.

Julian Layton, Correspondence, Wiener Library archives.

Australian National Archives.

Clare Ungerson, 2014, Four Thousand Lives: The Rescue of German Jewish Men to Britain, 1939.